I just stared… and stared… because that’s how photography works

There is one thing that every geek out there can agree on; mainstream media does not understand geek culture. The internet is a way to gather contacts for them, nothing more. They divorce themselves from all joy and stand on their pillars looking down on the world judging without any actual qualifications or experience.

Well, obvious hyperbole aside, it really doesn’t seem like the mainstream media is capable of understanding geek culture. Again, they send a general reporter to walk among super fans and the media comes out with a story condemning them for celebrating their passion. The piece “Awkward moments at Baltimore anime convention as art form comes of age” written by Josh Freedom du Lac for the Washington Post frames Otakon using the recent conviction of Michael A. Alper. Mr. du Lac never intended to write a story about the convention itself, he wanted to take advantage of a recent event and condemn the attendees of anime conventions for the perverts they are.

This style of journalism reminds me of Mark Twain’s story “How I edited an Agricultural paper” where the main character, after making up facts about agricultural in his featured pieces and being condemned for it confidently declares, “It’s the first time I ever heard such an unfeeling remark. I tell you I have been in the editorial business going on fourteen years, and it is the first time I ever heard of a man’s having to know anything in order to edit a newspaper.” That is, unfortunately, how the general media works. They can’t keep an expert on staff about every subject so they need to do the best they can with the best they have, and sometimes it backfires.

So now I present one of my patented deconstructions, a tactic that I do not employ often the most famous example being when Eric Sherman wrote his now infamous post declaring anime in the United States dead. This time is a little different, because I am dealing with someone who is coming completely outside the community. This time I’m not going to be arguing against this piece, because the vast majority of the anime community has already rejected the piece as alarmist and silly. My deconstruction this time will be far more humorous than intelligent commentary. I hope you enjoy it.

We begin with the title, “Awkward moments at Baltimore anime convention as art form comes of age” which really doesn’t mean anything. “Awkward moments at Baltimore Anime convention” sounds like a series of photos or a cute story of social awkwardness, not a piece that should run by a professional journalistic institution about dangerous perverts hunting down young girls. The accusation that anime is just “coming of age” is a bad pun. The article has nothing to do with anime as an art form, it’s simple being insulting and minimizing of a medium that has been around since the early 1960s and which exploded in the United States ten years ago. But, yeah, the Washington post needed a catchy title.

“Madoka! Madoka!” a man shouted, and the 16-year-old dressed as a 14-year-old Japanese cartoon schoolgirl stopped in the middle of the Baltimore Convention Center. “Can I take a picture?”

She nodded, then struck a pose as Madoka Kaname, the “magical girl” character she was dressed as last weekend at Otakon, the annual festival of Japanese cartoons that once again turned the Inner Harbor into the epicenter of all things anime.

Her costume included a Day-Glo pink wig with pigtails, white knee-high stockings, a red choker and a short pink-and-white dress that Little Bo Peep might have worn on a day she wanted to alarm her parents.

The man, who appeared to be in his mid-30s, pointed his digital camera at the make-believe Madoka, snapped a photo . . . and then stared.

And stared.

Josh Freedom du Lac doesn’t mention how polite the gentleman was when asking for the photo. Seemed like a nice guy, not some pervert with a zoom lens standing forty feet away and snapping photographs covertly. This was a man who shared an interest with the girl, and complimented her costume by asking for a photo. Of course, du Lac draws the scene to have you believe that this man was going to masturbate to the photo later in his hotel room. Jumping to conclusions a bit, aren’t we?

What does “stared” mean exactly? He was taking a photograph! I genuinely don’t look away from the subject I’m photographing. This sounds like perfectly normal behavior and the author wants to toss him in prison. Being a writer, du Lac might not be familiar with the careful art of photography. A basic principle of the process: Looking at your subject. The detailed description of the Madoka costume might make me believe that Mr. du Lac was staring at the young girl as well.

“It can sometimes be very weird,” the teenager said of her convention encounters with overly interested older men. “But they really don’t mean any harm.”

Between the photographer, the girl cosplaying, and the Washington Post writer observing the event the only one who seems to be worried about the exchange is du Lac, who was watching the 16 year old girl being photographed. Again, looking at the subject is a perfectly normal part of photography. But is staring at young girls a part of covering Otakon for the Washington Post? I’m questioning why they let this guy into Otakon; forget the forty year old anime fans.

This is a delicate time on the anime convention circuit, where a demographic shift has created an occasionally unseemly and sometimes dangerous dynamic.

Men have long been the foundation of the genre’s fan base, but they’ve been joined in increasing numbers by teen girls, whose embrace of the medium’s more fantastical side has helped launch anime to new levels of stateside popularity.

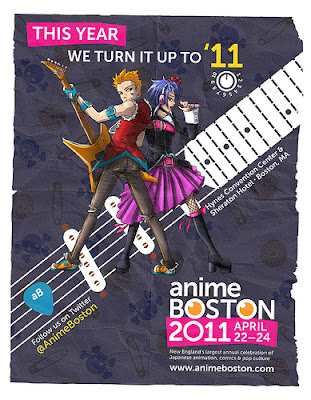

Men haven’t been the foundation of anime’s fan base, which is a medium not a genre, for over ten years. Even when I attended Anime Boston in 2003 there was a healthy number of fangirls, believe me I heard them during the Gundam Wing voice actor panel.

Conventions that were once cult gatherings attended almost exclusively by VHS-trading college-age (and older) males are now overflowing with young females, many of them sporting various iterations of anime’s popular doe-eyed, scantily clad look.

I really wish they would stop using the term “newspaper” because VHS-trading is in the ancient past of anime fandom. I don’t know where this guy is getting his information. Perhaps Usenet? Maybe he subscribes to a fanzine?

The author then goes on to discuss Katsucon’s policy change to check preregistration list against the sex-offender registry, a policy that the con-going community has universally declared alarmist and ineffectual. He actually asks one of the Otakorp board of directors if they’ll be instituting a similarly ineffectual policy at their convention.

Jennifer Piro, a member of the board of directors for Otakorp, the nonprofit group that produces Otakon, said that “no decision has been made” to introduce a similar policy at their convention.

Otakon, she said, has taken precautions to protect minors. All attendees younger than 12, for instance, must be accompanied by a parent or guardian at all times, and adult-themed programming is presented late at night, for those with 18-and-over wristbands. But, Piro said, Otakon “is not a babysitting service.”

I love how du Lac makes sure to highlight the quote “is not a babysitting service” as if Otakon is the villain for not thinking of all the young girls who might have their picture taken by older men. Nothing Piro told the Washington Post should be a surprise or a concern. The policies that anime conventions have to keep children away from material they shouldn’t see have always been in effect, and it’s rare when businesses want kids younger than twelve in their stores when not attended by an adult let alone a weekend long event with over thirty-thousand people. This isn’t news worth printing, this is standard convention policy.

“We want to do everything we can to keep our attendees safe,” she said. “But there’s only so much you can do. . . . There are definitely sketchy people out there. They could be at the mall. They could be at McDonald’s. This is still the real world.”

I love how Piro just destroys any argument that du Lac has in this piece with the quote above, and du Lac simply quotes it, ignores the wisdom of it, and continues with his alarmist message. Let me explain this quote to the author: Sketchy people don’t just go to anime conventions, anime conventions attract a large number of people and some people happen to be sketchy. In any large gathering you’re going to have an unsavory character or two hanging around. There are many places where young girl wear skimpy outfits. The beach, for one. Men with the Cameras won’t be asking permission for photographs at the beach.

Anime is a broad medium that ranges from the purely innocent to the pornographic. Some of it fetishizes young girls.

The Alper arrest and conviction became a hot topic among anime fans, some of whom fear being further stigmatized. (Many of them already think that other people consider them geeks who live in their parents’ basements.)

You’re the person who is casting that stigma on anime fans! This is a hit piece; don’t try to pretend like it is anything else. The reason why stigma exists on anime fans is because of people freaking out over a little pornography or some socially inept kid making a Death Note. Each time the media takes these stories and blows them out of proportion, because fear sells. Especially fear of those strange Japanese cartoons. Look at what du Lac wrote a little further in:

But an uncomfortable undercurrent is obvious. Just consider the visual snapshot of attendees at any anime convention now.

“You get hundreds and hundreds of young girls in skimpy costumes . . . and then you have older male anime fans,” Diederichs said. “The juxtaposition of the two may not look entirely wholesome.

So with one hand du Lac explains to his readers that male convention attendees don’t want to be stigmatized, and then he just manages to get a quote which declares that anime conventions are unwholesome places. I have a feeling his editor made him put in something from the side of the males, because the two quotes from Anime News Network forums where a user reacted to Alper by saying it will alienate him even more when he attends anime conventions seems out of place. I can’t help but think the ANN quotes weren’t used with some since of irony as du Lac spends the rest of the article condemning the content at Otakon.

Everywhere you looked, there were older girls dressed as little girls and little girls dressed as littler girls — and grown men taking photos of all of them. Sometimes, the men asked for hugs, too.

“There’s a little bit of perviness,” said Jamie Blanco, who was cosplaying a teenager from the hit anime series “Bleach.” (In real life, she’s in her 20s and the morning-drive producer for Federal News Radio.) The majority of people who attend anime conventions, she said, are there “because of a pure love” of the art form, its characters and stories. “But there are definitely a small percentage who come here to hug up on some of the younger girls — and younger boys.”

It’s disgusting how vile du Lac paints anime conventions. From his description, you’d think that the only reason anime conventions exist is to fetishize young girls. Never once is it mentioned that the reason most of the characters being cosplayed are teenagers or younger is because popular anime is generally targeted at teenagers. Would he feel as weird if a 25 year old was dressed as Hermione from Harry Potter? That also happens all the time at geek events.

The poor cosplayer he interviewed, Jamie Blanco, probably had no idea that the fact she was dressed as a teenager would be used against her. The only reason to point that out is to increase the perception that cosplay culture’s main focus is the fetishization of little girls. du Lac tosses in Blanco’s comment about the fans love for the art but that is lost in the paragraph because of the remark about her cosplaying a teenager and the quote the ends the paragraph, where Blanco states a coerced statement about perverts coming to hug young girls. Does that exist? I’m sure there are a handful of people, but framing it with remarks about the fetishization of young girls makes it sound like a widespread problem. As if the event’s goal is to give older men a chance to hug up on girls and girls dressed like little girls. Even if that isn’t du Lac’s goal, that is the message a paranoid person will walk away with.

At the trade bazaar in the bowels of the Convention Center, one could buy all the too-short schoolgirl outfits one would ever need. Also on offer: hentai, or pornographic comics, some of which leaned Lolita.

If I didn’t have you convinced of du Lac’s obvious distaste for Otakon this paragraph should change your mind. He calls the dealer’s room a “trade bazaar” hidden in the “bowels” of the convention center. That conjures an image of dusty tents manned by turban sporting con men, maybe with an eye patch or two. It certainly doesn’t give the image of the sterile concrete hall filled with book vendors and plastic dolls. The only items he tells his readers, a general audience most of which will never go to an Anime convention, are fetishized costumes and child pornography. Again, is du Lac telling the truth? Of course he is, that stuff is available at every anime convention I’ve ever been too. Du Lac is using it to take advantage of the emotions of his readers and sway them to accept his general thesis; Otakon is a dangerous place for young girls.

In 1994, before anime moved in from the outer edges of fringe culture in the United States, David Stoliker attended the first Otakon. He has turned out every year since. He is 43 now, a physical therapist from Long Island. His summary of the demographic shift at Otakon: “There are definitely people who can wear skimpier costumes a little better.”

I’m going to assume that quote isn’t completely taken out of context, perhaps after a ten minute conversation with Mr. Stoliker. Oh wait, no I’m not.

But don’t take that the wrong way, he said. Most of what happens at Otakon “isn’t prurient. It’s certainly not criminal.” An encounter like the one between a registered sex offender and a 13-year-old at Katsucon, he said, “can happen anywhere. People tend to draw attention to it when it happens in an unusual environment.”

Again, du Lac adds another tiny aside that states the obvious. Anime conventions aren’t hot beds of sex crime. It’s clear that du Lac doesn’t believe that. Every contrary opinion to the idea “Otakon is full of perverts” comes as a quote, never through the author’s own words, and this one is framed by the “skimpier customers” bit and the ending of the piece which recounts a Pedobear cosplayer’s antics. Any bit of the article meant to disrupt the author’s quest to slander the anime community is buried in a series of frightening descriptions and facts meant to lead readers into fearing Otakon.

A man dressed in a “Pedobear” costume was there, portraying the creepy satirical mascot that first emerged on the Internet as a way to mock inappropriate behavior in anime Web forums. Pedobears are regulars at anime cons, where many attendees appear to be in on the joke.

“Everybody loves Pedobear,” Travon Smith, the 20-year-old Baltimore man inside the sweltering teddy-bear suit, said — while assuring anyone within earshot that he is not, in fact, a pedophile. He also is not endorsed by Otakon but came to the conference as a paid attendee. “It’s all a joke,” he said. “Just people having fun.”

In his costume, Smith posed for photos and shook hands. People laughed. A young girl hugged Pedobear.

Clearly du Lac doesn’t want his readers to believe that Travon Smith is doing this “all in fun” but is somehow plotting to commit several dozen sex crimes… as girls voluntarily offer to hug him while he is wearing a cute bear suit. That’s the point of Pedobear. He is a symbol of innocence that is twisted by an idea of child pornography. He is a joke, an elaborate joke but a joke nonetheless.

Joking aside, Josh Freedom du Lac’s piece is nothing more than the worst kind of journalism. He went into Otakon with a story in mind; he was going to frame it with the sentencing of Michael A. Alper and point out how creepy anime conventions are. However, he doesn’t get any evidence to back that up besides his own skewed observations and some questionable quotes. Most of the quotes he uses can be summed up as “It isn’t that big a deal” and yet the author’s commentary of the convention makes it out to be an incubator for sex crimes. Because of this, the piece is poorly structured and the message is lost as he ping pongs between quotes from people who love anime culture and his dark views of the world of anime conventions. His observations, such as pointing out that everyone is cosplaying teenage girls or pointing out that Hentai is available at conventions, are obvious ploys to get the readers emotionally startled, thus bringing them onto his side.

The scary part is the readers of this piece. It’s aimed at an audience that is willing to believe that anime fandom, a classically misunderstood subculture in the United States, is full of perverts who lust after young girls. It is a borderline hit piece with the potential to force anime fans that are already reluctant to talk about their passion into a more reclusive position. This isn’t something the anime community needs, especially with the licensing industry finally stabilizing.

Will this article have any lasting affect? I doubt it. It certainly isn’t doing anything to improve the image of the anime community. Josh du Lac doesn’t give any mention of the $65,000 the attendees raised for Japan relief or how the community gives relief to people who otherwise feel out of place in their school or local community. No, du Lac writes about fear mongering because that’ll get more hits on the Washington Post website.

I’m sure among the 30,000 people who attended Otakon there were some bad seeds. However, as I’ve stated above, a public beach is a far more vulnerable location for young girls to hang out, and they are dressed in far less while sunbathing than they are while enjoying Japanese Cartoons. You also don’t need to pay admission to a beach, most of the time, yet because of Alper we get a piece on how dangerous anime conventions are. I’m sure most of it will be forgotten the next time a young girl gets raped at a mall.

The growth of Towa is heartbreaking as the audience slowly realizes how stunted her development has been by the disappearance. Makoto helps her open up by just interacting with her, something few have tired since her regression. As Towa becomes more familiar with her cousin she is slowly able to interact like a human being again. It’s an interesting exploration of mental illnesses like regression, disillusion, and being disconnected with reality. As Towa comes back to the world the damage done to her is apparent. The scenes where Makoto is being rough and pushy with Towa are some of the most touching of the series because in Towa’s reluctance are signs of what she has been going through as the world slipped away from her.

The growth of Towa is heartbreaking as the audience slowly realizes how stunted her development has been by the disappearance. Makoto helps her open up by just interacting with her, something few have tired since her regression. As Towa becomes more familiar with her cousin she is slowly able to interact like a human being again. It’s an interesting exploration of mental illnesses like regression, disillusion, and being disconnected with reality. As Towa comes back to the world the damage done to her is apparent. The scenes where Makoto is being rough and pushy with Towa are some of the most touching of the series because in Towa’s reluctance are signs of what she has been going through as the world slipped away from her.

the series. She appears in one major scene which is mostly humorous and works to destroys some of the realism that Denpa Onna had tried to maintain. Yashiro, at best, distracts from both the romance story and the relationship Makoto has with Towa. I don’t know why she had to be included in the narrative, and the only reason I could think is that SHAFT believed that more Moe characters would translate to more profit.

the series. She appears in one major scene which is mostly humorous and works to destroys some of the realism that Denpa Onna had tried to maintain. Yashiro, at best, distracts from both the romance story and the relationship Makoto has with Towa. I don’t know why she had to be included in the narrative, and the only reason I could think is that SHAFT believed that more Moe characters would translate to more profit.

participate in a gaming tournament but this year they allowed members who simply borrowed games to earn tickets. Anyone can earn tickets simply by hanging out in Board Gaming and enjoying some games. The tickets can be redeemed for prizes, the selection of which is as varied as the types of games available at the convention. Most Dungeons and Dragons book you’d want, dozens of other lesser known RPGs, Magic Cards, dice, and a score of high quality board games. At ConnectiCon if you spend a couple of hours playing board games with friends or strangers you could walk out with a $50 board game. That alone pays for the weekend.

participate in a gaming tournament but this year they allowed members who simply borrowed games to earn tickets. Anyone can earn tickets simply by hanging out in Board Gaming and enjoying some games. The tickets can be redeemed for prizes, the selection of which is as varied as the types of games available at the convention. Most Dungeons and Dragons book you’d want, dozens of other lesser known RPGs, Magic Cards, dice, and a score of high quality board games. At ConnectiCon if you spend a couple of hours playing board games with friends or strangers you could walk out with a $50 board game. That alone pays for the weekend.

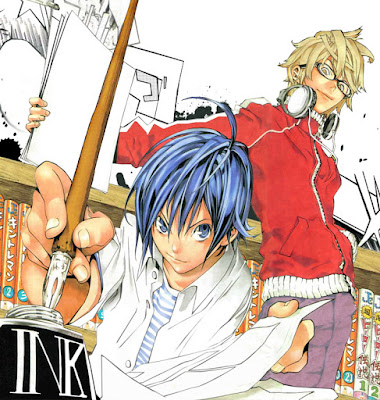

It’s hard not to compare Bakuman to Death Note, Ohba has a narrative style that commands the attention of the audience and adds suspense with surprising regularity. One could claim that the idea itself is what really kept people interested in Death Note, but now that Ohba has applied that style to the rather mundane story of two kids writing comics and made it just as intense as Death Note, so clearly he has unlocked a structure and pacing that simply works. The impact of cliffhangers is such an important and difficult aspect in serialized content and yet Bakuman is able to create a compelling stopping point nearly every episode with story lines like “will they meet their dead line” or “What will happen when they meet with the manga editor.”

It’s hard not to compare Bakuman to Death Note, Ohba has a narrative style that commands the attention of the audience and adds suspense with surprising regularity. One could claim that the idea itself is what really kept people interested in Death Note, but now that Ohba has applied that style to the rather mundane story of two kids writing comics and made it just as intense as Death Note, so clearly he has unlocked a structure and pacing that simply works. The impact of cliffhangers is such an important and difficult aspect in serialized content and yet Bakuman is able to create a compelling stopping point nearly every episode with story lines like “will they meet their dead line” or “What will happen when they meet with the manga editor.”

The characters are also subject to the same derivative problems. The protagonist falls in love with Phryne, the girl he saved, almost instantly and makes it his job to protect her. That becomes the single motivating factor for all his actions in the series. While that is an anime cliché there is some realism to it because of the way Clain has been living. Realistically, this is the first young girl that Clain has ever seen and there is probably an overwhelming fear that he might not see another woman in a long time living in the middle of nowhere and refusing to take advantage of Fractale. Even so, Clain is a bit of an anomaly because while the population of the planet doesn’t seem as large as it is today, there are children inhabiting the world of Fractale and Clain’s very existence implies that his problem is odd. So the explanation doesn’t really hold water except that Hiroki Azuma, original story creator, created a character that fit perfectly into that cliché without thinking about how the vast, network connected world’s effect on human relationships. What could have been an interesting narrative jumping point is squandered for a cheap cliché.

The characters are also subject to the same derivative problems. The protagonist falls in love with Phryne, the girl he saved, almost instantly and makes it his job to protect her. That becomes the single motivating factor for all his actions in the series. While that is an anime cliché there is some realism to it because of the way Clain has been living. Realistically, this is the first young girl that Clain has ever seen and there is probably an overwhelming fear that he might not see another woman in a long time living in the middle of nowhere and refusing to take advantage of Fractale. Even so, Clain is a bit of an anomaly because while the population of the planet doesn’t seem as large as it is today, there are children inhabiting the world of Fractale and Clain’s very existence implies that his problem is odd. So the explanation doesn’t really hold water except that Hiroki Azuma, original story creator, created a character that fit perfectly into that cliché without thinking about how the vast, network connected world’s effect on human relationships. What could have been an interesting narrative jumping point is squandered for a cheap cliché.

While Fractale offers an interesting world with some stunning animation the show is weighed down by anime cliché and Meta elements that give the show a patched together feeling. While it attempts to reach far and build an epic storyline, it fails to reach any new ground. Fractale isn’t awful, it is just a forgettable show and the community at large, including myself, has been harsher on Fractale because of the promise Yutaka Yamamoto gave to the audience. There is a quality series here, but it’s hidden under incompetent directing and no clear narrative vision.

While Fractale offers an interesting world with some stunning animation the show is weighed down by anime cliché and Meta elements that give the show a patched together feeling. While it attempts to reach far and build an epic storyline, it fails to reach any new ground. Fractale isn’t awful, it is just a forgettable show and the community at large, including myself, has been harsher on Fractale because of the promise Yutaka Yamamoto gave to the audience. There is a quality series here, but it’s hidden under incompetent directing and no clear narrative vision.